err/er,ər/

verb

be mistaken or incorrect;

to make a mistake

“We got your prime pilots that get all the hot planes, and we got your pudknockers who dream of getting the hot planes…see, some peckerwood’s gotta get the thing up and some peckerwood has gotta land the son of a bit**. And that peckerwood is called ‘a pilot.’”

–Pancho Barnes, “The Right Stuff”

According to The Oracle of The Happy Bottom Riding Club, we are either pudknockers or prime pilots and all of us that take off and land airplanes are peckerwoods. But are pilots human? Of course we are, but after 100-plus years of manned flight, in the eyes of most people that are not pilots, the mystique of flying remains exciting, dangerous, difficult, romantic and sometimes a bit superhuman. And they expect all of us pudknockers and prime pilots alike to be error-free. When I was a silver-reflective-sunglass-wearing teenage private pilot (wow, that’s a mouthful), I had a T-shirt that said: “To Err is Human; To Forgive is Out of The Question.” The term for making a mistake in baseball is an “unforced error.” And I made one in MIA, felt like a pudknocker, and I’m having trouble forgiving myself.

Head Games

Other than the cost of learning to fly, the aforementioned exciting, superhuman mystique is likely the reason most pilot wannabes continue to be wannabes. And why some who become pilots are reluctant to learn to fly more complex machines or in more challenging environments. No one wants to feel like a pudknocker by meandering too far from their comfort zone. It’s that mentality that kept me from becoming a professional baseball pitcher, applying to the USAF Academy and dissuaded me from any type of engineering profession because those folks are more disciplined, more talented, smarter and able to learn much easier than me.

So, how did I get past that mentality to become a steely-eyed fighter pilot, airline captain and brilliant writer? I forced myself to become disciplined and focused, which eventually gave me skill (if not talent). And by working longer and harder than my peers (I know, everyone says that), I slowly learned to fly airplanes and write magazine articles. And even though flying an F-16 gave me FPAS (Fighter Pilot Arrogance Syndrome), my occasional unforced errors in piloting nowadays are an effective therapy in correcting this annoying personality flaw – mostly.

Perceptions

Over the years, the public has grown to believe that the superhuman part of piloting is only needed for the first and last ten minutes of a flight. Ask most travelers how we are able to fly from A to B while in the rain, snow and gloom of night from lift-off to touch down, and they will say that ATC, radar, GPS and autopilots are making all of the brilliant maneuvers and flawless approaches. Unmanned drones are not helping with this mindset. If it was a bumpy flight, if it takes longer than planned, or if we make a bad landing, then we must not have listened to ATC, we turned off the autopilot or we are simply ham-fisted pudknockers. With our modesty in check, we can do our best to clarify this perception and promote the piloting profession.

When I make a PA to the pax about the ride ahead, I always say that pilots above, below or out in front of us are saying it will be smooth or bumpy. Yes, we get that information from ATC and I’m grateful, but they got it from a pilot, not radar, GPS, an autopilot or their ride-forecasting Ouija board – they got it from a pilot. Whenever a passenger gives us a compliment on the trip, in-flight PAs or the landing, I’m grateful and contrite (FPAS notwithstanding) as I smile through my COVID mask, nod and say thank you. And when the FO flew the leg, I always say it was the copilot’s leg and landing, not the first officer but the copilot. I want for them to hear the pilot word. But on this day in MIA, I was disappointed in myself as a pilot not only because it was my error that created the need to go-around, but I lied to my passengers about the reason I did it. Here’s the truth.

Arrogance Syndrome Rehabilitation

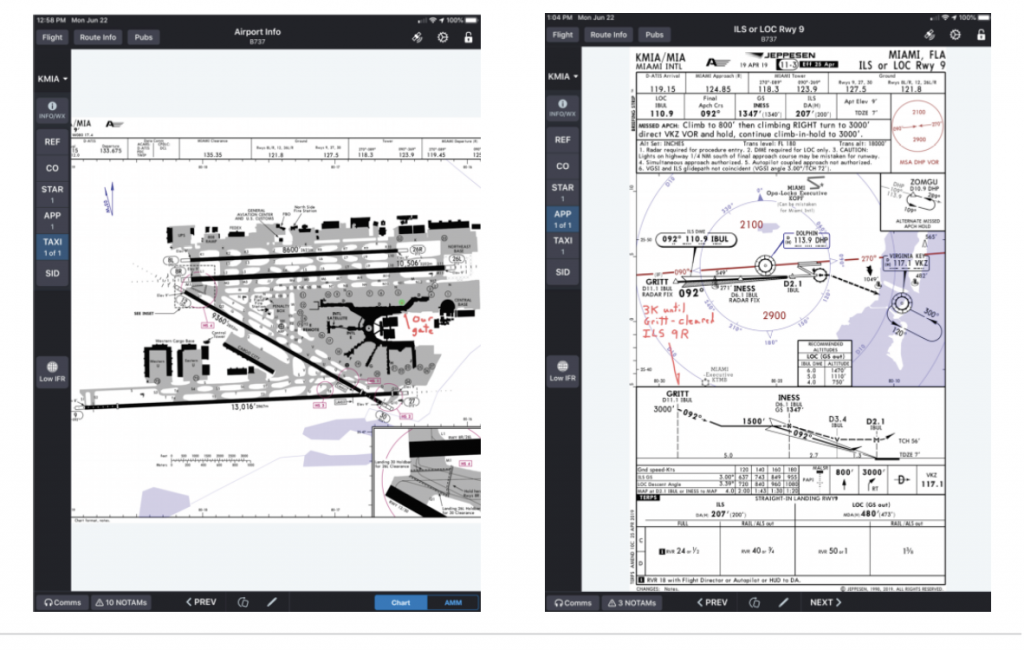

There I was, in my painted 737 (as opposed to a shiny MD-80). It was a one-leg day, ORD to MIA, in daylight, decent weather, with a 24-hour layover in a COVID-ruled hotel with a COVID-ruled, but delicious, seafood restaurant next door. The trip signed in at 0415 for a 0515 departure so we were finished and in our hotel rooms by 1000. My FO and I hadn’t flown together yet on the 737 but had been paired together a handful of times in the Mad Dog. Except for the 0245 alarm clock, it’s an easy peasy trip – not hours of boredom punctuated by moments of terror. The two-hour flight was, however, punctuated with the MIA-typical runway selection/change ritual in the last few minutes. I had done this trip four or five times in the previous couple of months and since our gates are on the north side of the terminal, we had repeatedly been assigned one of the north-side runways: 8R ILS or 8L RNAV GPS, all from the SSCOT-5 RNAV arrival.

Knowing this in the descent, I loaded and briefed the 8L RNAV GPS because it’s easier to switch to the ILS from the RNAV than to switch to the RNAV from the ILS. But this time we got the ILS to 9R – no big deal. The process of flying an approach includes loading the FMS, tuning and identifying the NAV radios, setting the radar and baro. altimeter mins, then briefing the approach to the other pilot. We have acronyms to help remember the process, including the FMS steps: “check-plus-two” covers the FMS and setting up the HUD. A semi-optional step is to use the fix-page to put a 2-mile ring around the FAF/glide path intercept point. This gives us a heads up to intercept the descent path and finish getting configured.

I forgot this step. The 2-mile ring step, not the get configured step, and it bit me in my lazy hinny. Not because I skipped it, but because I tried to complete the step instead of a more important step, which was pushing the GS capture button. I instead created the 2-mile ring around INESS. We were level at 3,000 feet, in the weather at GRITT, and by the time I finished creating the ring and armed the GS capture mode, we were past the descent path and too far above the glide slope to salvage a stable approach. After we went around, I told my passengers that we were too close to the aircraft landing in front of us. I lied – what a pudknocker.

At Home in the Sky

A well-adjusted person is one who makes the same mistake

– Alexander Hamilton

twice without getting nervous.

I’m coming up on 30,000 hours in the sky: 2,000 military, 2,000 in the Guppy, 18,000 in the Mad Dog and the rest in GA. Comfortable and confident describes how accustomed I am to being in an airplane. Oftentimes my biggest threat of the day is not overconfidence but being complacent – lazy. Like when you think to yourself that it feels as if the car knows its own way to the office. I’ve got to stay more focused and maybe stop going to Florida. The battery in my C-150 overheated near TPA; I had a near mid-air between my Cherokee and two F-4s in South Florida; I had to jettison some malfunctioning, inert F-16 ordnance off the coast of MIA; and I sucked a bird down the intake between MIA and the Avon Park bombing range. The right engine of my MD-80 blew up at gear retraction in MIA (see “Issues,” T &T September 2010), and I allowed my FO to bust an altitude on approach into MIA. Now I’ve committed an unforced error by forgetting to arm the GS mode which dictated a go-around – also in MIA. I’m seeing a sunshine state trend. We were still 20 minutes early at the gate, but I was disappointed in myself for the mistake and the lie.

The Spirit of Pancho Barnes

The malfunctioning 500-pound Mark-82 bombs and the MD-80 engine failure were not my fault, nor was the C-150 battery malfunction, the near-midair nor the bird-sucking event. And a go-around for any reason is not a mistake. But the ILS switch error made me feel like a student pilot and not at all superhuman – like an unfocused, let-the-car-find-its-own-way pudknocker. To err is human indeed, but I didn’t like the smirk that I imagined on Pancho’s face as she shook her head and called me a (expletive) pudknocker.

But I’ve learned that a stable approach ranks right up there with not stalling the airplane, not hitting anything with the airplane and not running the airplane out of gas. Flying a stable approach is one of the most important things that we do. Many of us are just now getting back into the saddle after the COVID lockdown, and we’re once again flying in some serious rain, snow and gloom of night – OK, maybe not snow yet. Stay focused and stay ahead of the airplane, my fellow peckerwoods. The spirit of Pancho Barnes is watching.

Author’s Note: Since mid-June when I wrote this article, I’ve added another reason to avoid Florida. It looks like the positive COVID test I received on June 29 was a result of time in MIA. Mine was a “relatively” mild case (102.9 temp, lost 15 pounds in 7 days, no smell or taste, flu-like pains and quarantined/off work for three weeks) but even still – I strongly recommend following CDC guidelines. And yes, I was wearing a mask constantly except when in the cockpit.