I hate the approaches to JFK.

There, I said it. If you are one of the unfortunate pilots required to attend simulator training every year, you know exactly what I mean. I can almost hear a loud “Amen!” followed by laughter. You hate JFK approaches, too, right?

I have no idea why, but every single simulator operator seems to use the approaches for John F. Kennedy Airport (KJFK) for every training event – every. single. time. The training never changes. There must be some kind of rule. Perhaps it’s a secret handshake given to pilots who lose their medical certificates and become flight simulator instructors. Maybe there’s a simulator mafia that will punish you if you dare to do something different. I’m convinced there’s a financial retirement fund available only to simulator instructors who use the JFK approaches. It simply never changes.

Training always begins with a hot start on one of the engines (which gets quickly repaired), followed by a blind taxi on an empty, unmarked ramp to an unmarked runway (really? Why even include taxi training in a simulator?). Then, there’s a normal takeoff on RWY 13R with vectors to the “practice area” (whatever that is – we all know it doesn’t exist anywhere near JFK) to perform stalls and steep turns. Next, you magically appear on a long downwind for the ILS RWY 4R approach, which always ends with a complicated missed approach to a hold. The weather mystically improves, and suddenly, the ILS RWY 4R circle to RWY 31R seems appropriate, but this time you’ll make a full-stop landing. The takeoff on RWY 31R will conclude with an engine failure after V1, leading to a turn back to the JFK VOR to fly the full VOR 4R approach. Of course, the weather unfortunately deteriorates, and you must execute a single-engine missed approach to return for the ILS, which mercifully ends in a full-stop landing – although the flaps didn’t work on the approach.

That’s it. That’s what you do every year, with every instructor, in every simulator that has ever existed. They always have a “pre-brief” in the briefing room, but there’s really no need for it. We all know what to expect. I first encountered the “JFK approaches” in 1999 when I began training at American Eagle Airlines as a Saab 340 First Officer. I flew that profile back then, wondering if I’d ever see those approaches in real life since American Eagle operates from JFK.

A Simism refers to the method a pilot learns to operate the simulator in ways that only apply to that environment and have no basis in real-world flying.”

My time with American Eagle lasted only two years before I could no longer survive on the $17,000/year salary (yes, you read that right). I resorted to stealing oatmeal from hotel breakfast offerings and literally ate oatmeal for two meals a day for two years while trying to support a family of five as a regional airline pilot. September 11th, 2001, changed the world for everyone, myself included. I resigned my airline aspirations and began a career as a flying salesman, using a Piper Mirage (PA46). I flew that airplane for eight years, logging about 500 hours each year and accumulating 4,000 hours of Mirage flight time, which connected me to one of the coolest communities ever – the Piper M-Class community.

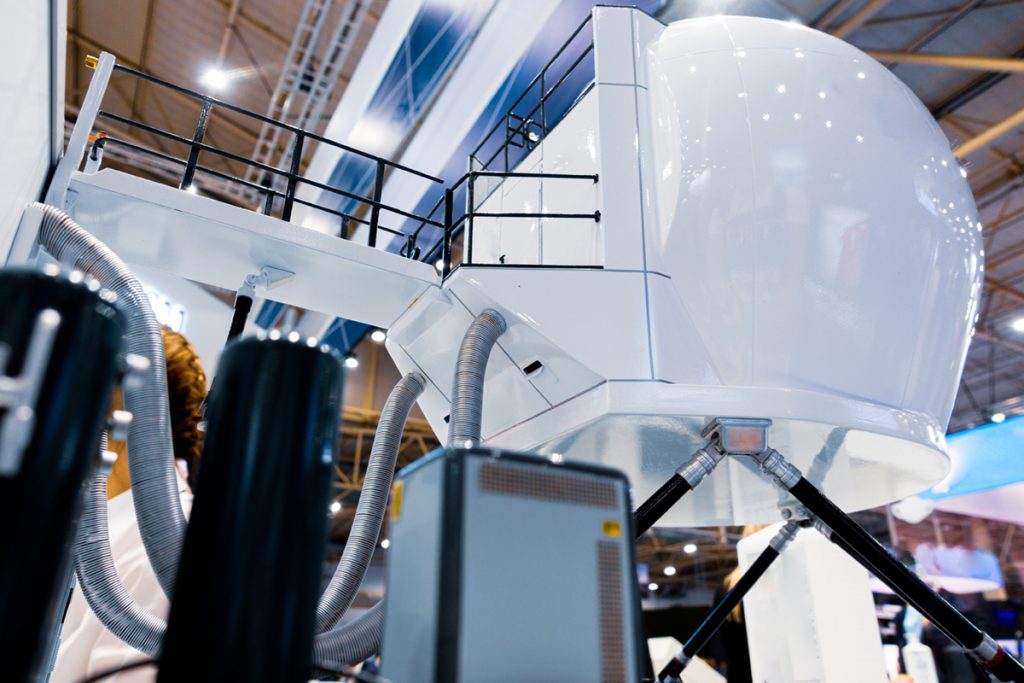

However, a local businessman purchased a King Air and requested that I fly his airplane as a part-time corporate pilot. I agreed and attended King Air flight training in what was arguably the worst flight simulator ever built. To be honest, it wasn’t even a “real simulator,” but an Advanced Aviation Training Device (AATD) – the lowest tier of training device that qualifies for training – and this one was on its last legs. It broke down at least five times in each training session. Of course, it came with a packet of well-worn, Xeroxed JFK approaches stapled together and carelessly tossed in the “window sill” by the unfortunate soul who endured the previous training session. Those notes from the last 5-10 pilots contained scribbled reminders about the nuances of the approaches that could be tricky during the checkride portion of training.

Another local businessman bought a Cessna Citation II, allowing me to attend a six-day simulator training event in Dallas, TX, at CAE. That simulator was aequally challenged. It only had a non-WAAS Universal GPS for navigation, their upgrade to the old turn-dial VORs. The avionics in this simulator were ancient, with no relation to modern systems found in current airplanes. And the only approaches that could be downloaded to the outdated Universal GPS were…you guessed it…approaches to JFK.

The simulator instructor had to pause the simulator to download the approach because half of the GPS buttons no longer worked, requiring a workaround to program an approach (which didn’t function like it does in the real world). We had to unpause the simulator only when the unreliable Universal GPS could be petted enough to work adequately. Somehow, I managed to get through that training event with a new type rating.

I remember taking off with a load of passengers in the actual jet after training, despite having never flown a jet before in my life. I had to teach myself how to operate the avionics installed in the jet I was flying. The training event was atrocious, irrelevant to “real world” jet flying, and a complete waste of time—it was only worthwhile for gaining credentialing. However, I definitely knew how to fly those approaches to JFK.

I think simulator instructors prefer using JFK because it has four runways: two parallel to each other and two perpendicular to the first two. This configuration makes it easy to conduct a circling approach in a simulator. There’s only a 90-degree turn required (instead of a more challenging 180-degree turn back to the opposite runway), and there’s a clear cue to start the turn. In a simulator, a smart pilot will begin the turn to final approach when the first perpendicular runway disappears from the left side of the TV screen. It’s an excellent cue to initiate the turn. While this may not reflect realism elsewhere in the real world, it simplifies landing from a circling approach during a checkride, which is ultimately the goal of a simulator company. They essentially operate as a pilot mill, aiming for pilots to pass their checkrides, provided they favor the pilot during training. Conversely, if an instructor is not fond of a trainee, they are unlikely to share helpful “simisms” for flying the circling approach. It’s much easier for a trainer to fail a pilot who struggles to locate the runway in a subpar nighttime simulator at JFK. In other words, “the simulator can be taught.”

This brings us to the term “Simism.” While this word may not be found in any dictionary, any pilot who has undergone simulator training as a professional will recognize it. A Simism refers to the method a pilot learns to operate the simulator in ways that only apply to that environment and have no basis in real-world flying. It’s when a pilot is taught to fly the simulator differently than in a real-world scenario to pass the checkride by adhering to these “Simisms.” For example, “The fuel flow meter doesn’t work, and we don’t intend to fix it, so just ignore that” is a Simism. Another would be if the simulator freezes even though you executed the approach perfectly, forcing you to restart—that’s a Simism. Or, “When landing, the simulator isn’t very realistic, so just pull the power to idle, hold the rudder pedals perfectly still, and don’t worry about being on centerline”—that’s also a Simism.

And the simulator with the most Simisms? The Embraer 120 simulator in Atlanta. I initially felt excited to become an Embraer 120 pilot, but first, I had to endure a two-week simulator course in what was likely the most outdated still-operational simulator. In the world of simulators, this one was a dinosaur. Yet it continued to operate 24/7. I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a dedicated maintenance team just to keep it functional, given how often it broke down. I’m not sure how we finished training with so many inadvertent screen freezes.

To keep the training on track through the frequent breakdowns, the instructors relied on their familiarity with the “JFK profile.” Thus, yet again, I found myself flying around JFK. I couldn’t help but laugh out loud when I sat in the briefing room to discuss the JFK approaches we were about to practice.

Do I have a chip on my shoulder? Yes! As I write this on the final day of my 22nd annual King Air recurrent training, I just flew the approaches to JFK once again. I trained in a Redbird AATD that malfunctioned four times during a two-hour session. We couldn’t operate the simulator with “motion on” because, as the instructor put it, “it would only make you sick, not a better pilot, because it is so unrealistic.” I flew those same approaches to JFK. The whole time, I felt like I was simply “going through the motions” (pun intended), not learning anything new, and merely “checking the box.” I genuinely think I would be a worse pilot after that simulator training experience if I followed the “Simisms” taught in that simulator.

We’ve established a “cooperate and graduate” culture in simulator training, where the same procedures are followed consistently across all airframe types each year. Instructors train using JFK approaches because that is how they were taught. Simulator instructors must also “cooperate and graduate” to keep their jobs. Unfortunately, many simulator instructors haven’t flown a real airplane in decades and have lost the tactile understanding of what actual flying is like. They tend to stick rigidly to the profiles they’ve learned, often hesitant to deviate even slightly. I doubt anyone has flown the “VOR approach to RWY 4R, Circle to Land 31R at JFK” in a real airplane in years. Yet, I would wager that 60% of the professional pilot population has executed that approach multiple times during check rides in the past year. It’s time for a change.

While I don’t expect this article to revolutionize the simulator industry, and I believe insurance underwriters will continue to mandate simulator training, it falls on pilots to supplement their training with additional credentials and experiences that enhance their skills and resumes. Do you have a glider license? A CFI rating? An ATP? A helicopter license? In my experience training pilots in PA46s, TBMs, and King Airs, those who are cross-trained, especially in helicopters, generally demonstrate better flying skills. The point is to broaden your horizons by engaging in training that diverges from your usual focus. Consider attending a mountain flying course, becoming a powered paraglider pilot, or learning to sail. Do something aeronautical that is different from your routine.

I hope to never see the “VOR approach to RWY 4R, Circle to Land 31R at JFK” again—I’ve been there, done that, at least I’ve simulated being there, simulated doing that.

Fortunately, graciously, the EMB-120 simulator in Atlanta was shut down in December 2023. As an experienced DPE, I was invited to become a DPE with credentials to administer the EMB-120 Type Rating. Now, EMB-120 operators conduct all their training in real airplanes. I’ve administered around 20 type-rating rides so far, and I’m truly impressed by how pilots have mastered that overly complicated aircraft. There are no longer any “Simisms” in the EMB-120, nor will we see the “VOR approach to RWY 4R, Circle to Land 31R at JFK” in the simulator. The EMB-120 community has been compelled to embrace change in training, and they have adapted remarkably. The EMB-120 continues to fly cargo boxes all over the world, but there will never be another EMB-120 flying box (simulator).

Please let me know if you know of a King Air trainer that does not operate a simulator utilizing JFK approaches. I’m looking to do something different during my annual recurrent training in the King Air next year. I’m tired of JFK approaches.