Page 17 - July22T

P. 17

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause of this accident to be: The pilot’s loss of airplane control due to spatial dis- orientation while operating in night, instrument meteorological conditions.

This is (Not) Only a Test

It’s easy to dismiss this triple-fa- tality tragedy as a “VFR into IMC” loss of control, tell yourself “I’d never do that,” and move on. In part that’s true, but this crash – and many more like it, often flown by highly quali- fied pilots – points to another high- risk activity: the first few minutes of flight. Especially if it is your first flight of the day or the first flight of the day in a particular aircraft. The first moments of a flight are a test for both you and the machine.

Are you at your A game, that is, doing your very best from the begin- ning? Or do you need a few minutes to get back into your groove? Will the airplane perform perfectly, or is there a discrepancy that won’t become ob- vious until the airplane is in the air? You won’t know for certain until you take off. It’s a test, but it’s not only a test. You and your passengers must live with how you and the air- plane fly before you’ve had time to catch up or to prove the airplane’s systems and equipment are set and working correctly.

Risk and Scrutiny

Any flight requires a serious eval- uation of risk and detailed scrutiny. But unlike physical activity, play- ing a musical instrument or even public speaking, we don’t really have a “warm-up” period before we begin a flight. We can inspect the airplane meticulously in preflight and follow Before Takeoff checklists precisely. But some mechanical and software-driven things don’t reveal their true working nature until fired up and in flight.

So what can we do? Unless you are extremely current and the airplane is regularly flown, think hard before launching into instrument condi- tions or at night (and certainly into a combination of the two). Regula- tions and tradition have us gauge

our proficiency based on arrivals – the number of landings in the previ- ous 90 days for carrying passengers, the number of approaches for flying under IFR. Perhaps we should have another column in our logbook to track actual and simulated instru- ment departures. Unless a pilot has logged a departure (or six) into instru- ment conditions in the previous six months, actual or simulated, then that pilot might limit themselves to marginal VFR conditions for depar- ture in the daytime or full visual meteorological conditions at night until resetting that currency counter. It’s as vital to proficiency as counting approaches, in my opinion.

It’s unlikely 14 CFR 61.57 will be up- dated to include such a requirement, and no doubt the “alphabet organi- zations” would fight it if FAA tried. But it’s not a bad idea as a personal minimum to help cover for the fact we (or the airplane) may need just a little time to show our true ca- pability as it exists in the first few minutes of f light.

Stack the Deck

You can do a lot to make the first few minutes easier and safer. Here’s one example:

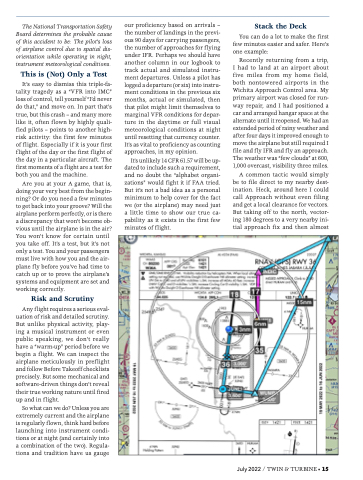

Recently returning from a trip, I had to land at an airport about five miles from my home field, both nontowered airports in the Wichita Approach Control area. My primary airport was closed for run- way repair, and I had positioned a car and arranged hangar space at the alternate until it reopened. We had an extended period of rainy weather and after four days it improved enough to move the airplane but still required I file and fly IFR and fly an approach. The weather was “few clouds” at 600, 1,000 overcast, visibility three miles.

A common tactic would simply be to file direct to my nearby dest- ination. Heck, around here I could call Approach without even filing and get a local clearance for vectors. But taking off to the north, vector- ing 180 degrees to a very nearby ini- tial approach fix and then almost

July 2022 / TWIN & TURBINE • 15